Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and Patents

For public companies in intellectual property–driven industries like pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and medical devices, patent portfolios are not just business assets—they are often the bedrock of long-term value. When those portfolios are inaccurately disclosed or misrepresented in ongoing filings, the consequences go beyond business risk. They may give rise to securities fraud liability under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

Under this Act, public companies are subject to ongoing disclosure obligations, including annual 10-K and quarterly 10-Q reports. When these filings include misleading or incomplete information about key patent assets, executives and companies alike may face serious exposure—particularly under Rule 10b-5, the SEC’s primary antifraud provision.

The Purpose of the ’34 Act: Ongoing Market Transparency

Unlike the Securities Act of 1933, which focuses on the initial offering of securities, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 is concerned with the ongoing integrity of the marketplace. It mandates continuous disclosures so that investors have up-to-date, accurate information about the companies they invest in.

That means your company’s 10-Ks and 10-Qs must fully and fairly disclose all material information, including risks or developments related to your patent portfolio—especially when those patents are central to your commercial strategy.

Rule 10b-5: The Core of Securities Fraud

Rule 10b-5, promulgated under Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, makes it unlawful:

“To make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made… not misleading.”

— Rule 10b-5, 17 C.F.R. § 240.10b-5

This rule applies not only to intentional fraud but also to reckless misstatements—such as omitting that a key patent has expired, is being challenged in court, or has become unenforceable due to prior misconduct or improper maintenance.

Why Patent Misstatements Matter

In high-IP sectors, investors routinely rely on assumptions about patent exclusivity and enforceability. If a company continues to report a patent as active or critical without disclosing its actual legal status—or omits ongoing reexaminations, litigation, or abandonment—the omission could be material under securities law.

Here are a few real-world examples that could create exposure:

-

Failing to disclose that a key patent expired due to non-payment of maintenance fees

-

Omitting material information about patent litigation that could invalidate a drug’s exclusivity

-

Reporting a large number of “issued patents” without clarifying that many are design patents with limited commercial scope

-

Continuing to list a patent as core to a product’s protection after its claims have been narrowed or canceled in post-grant proceedings

What Makes a Patent Disclosure “Material”?

Materiality is judged from the perspective of a reasonable investor. Would the omitted or misstated information alter how they view the company’s prospects?

In industries where a single molecule or device is protected by a single critical patent, the enforceability of that patent is unquestionably material. The failure to disclose risks affecting its validity or scope could lead to both SEC enforcement and private litigation under Rule 10b-5.

10-Ks, 10-Qs, and the Need for Accuracy

Form 10-K (annual) and Form 10-Q (quarterly) require companies to disclose:

-

Legal proceedings (Item 3 of Form 10-K, Part II Item 1 of 10-Q)

-

Risk factors, including risks relating to intellectual property (Item 1A of Form 10-K)

-

MD&A (Management’s Discussion and Analysis) of known trends and uncertainties affecting the company’s financial condition

If patent-related litigation, expirations, or enforceability challenges are ongoing or reasonably expected, they must be disclosed in these sections.

“A lawsuit that threatens a key patent’s validity isn’t just a legal problem—it’s a 10-K problem.”

Who Can Be Held Liable?

Liability under Rule 10b-5 extends to:

-

The company

-

Individual executives (especially signatories of the filings)

-

Investor relations and compliance officers

-

In some cases, outside advisers who help prepare disclosures

Private plaintiffs can sue under Section 10(b) and Rule 10b-5 if they purchased or sold securities in reliance on a misleading statement and suffered damages when the truth came to light.

The SEC can also bring civil enforcement actions for misleading disclosures, even without investor losses.

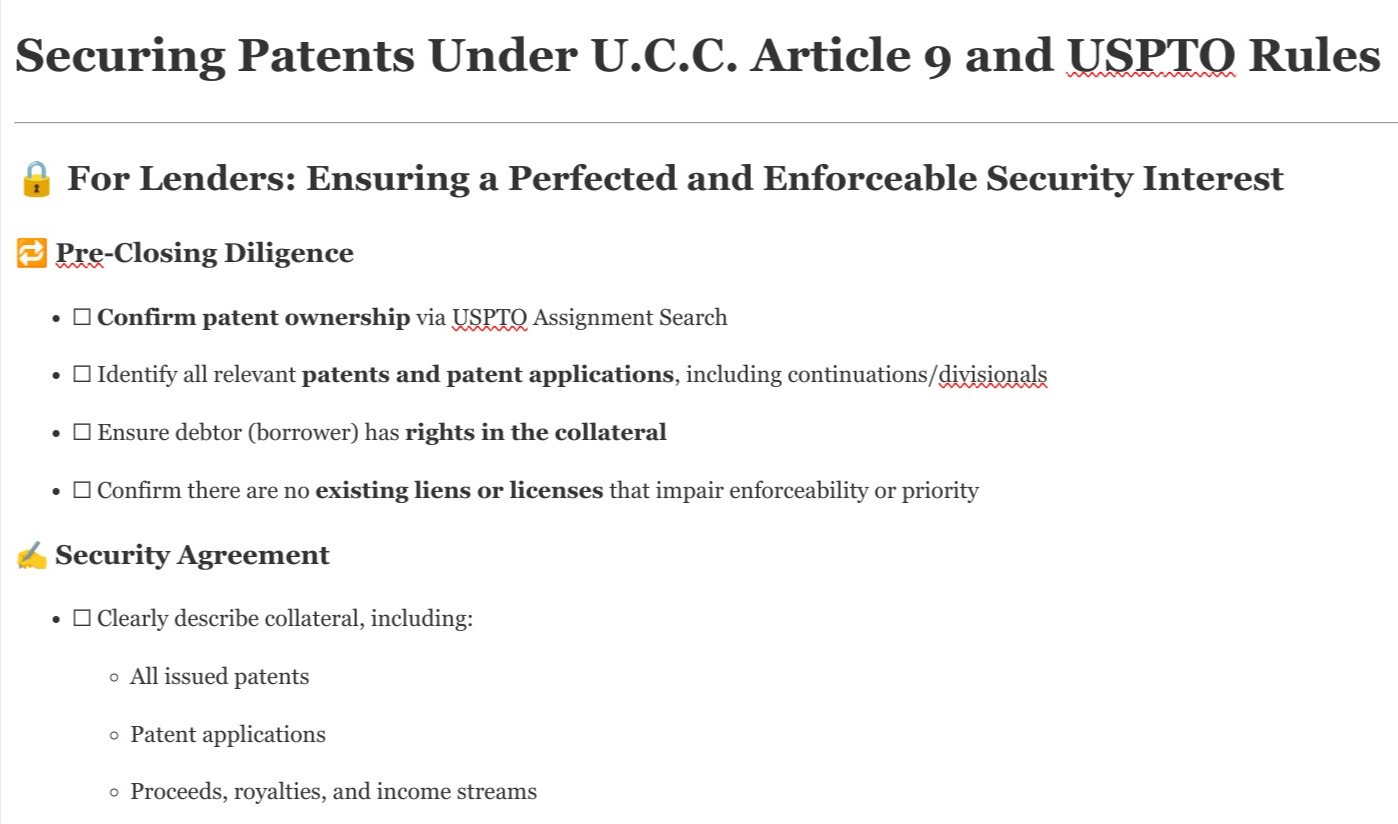

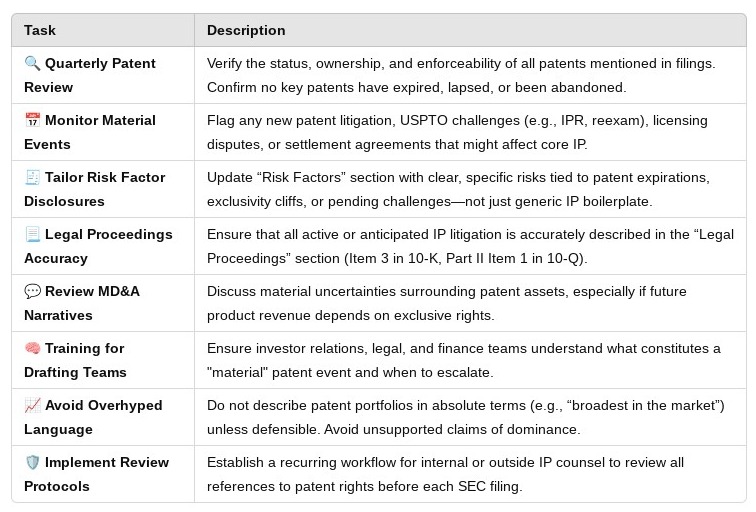

How to Reduce Exposure: Executive Checklist

-

Audit Your IP Disclosures Quarterly

Collaborate with in-house or outside IP counsel to confirm the accuracy and currency of any reported patents. -

Disclose Risks Clearly and Specifically

Generic language about “IP challenges” won’t suffice. Be candid about reexams, litigations, and expirations. -

Train Your Reporting and Legal Teams

Make sure those drafting the 10-K and 10-Q understand how to evaluate and disclose IP-related risks. -

Avoid Overly Promotional Language

Don’t characterize the patent portfolio in absolute terms if there are known vulnerabilities or dependencies.

IP Reporting is a Securities Law Issue

Patent disclosures are not just technical or legal matters—they are securities disclosures subject to Rule 10b-5. In an environment where market value often hinges on future exclusivity, accuracy and candor about the scope, enforceability, and status of patents is mandatory.

Failing to disclose a lapsed or contested patent might not only impact your valuation—it could result in securities fraud litigation.

“The more central a patent is to your business, the more central it is to your disclosure obligations.”

Further Reading:

Additional Insights

news via inbox

Nulla turp dis cursus. Integer liberos euismod pretium faucibua